The mission is to tell the stories…”

Paul Zimmerman in conversation with Steve Alpert

Paul Zimmerman: Your subjects include landscapes, portraits and military themes. Why are they important for you?

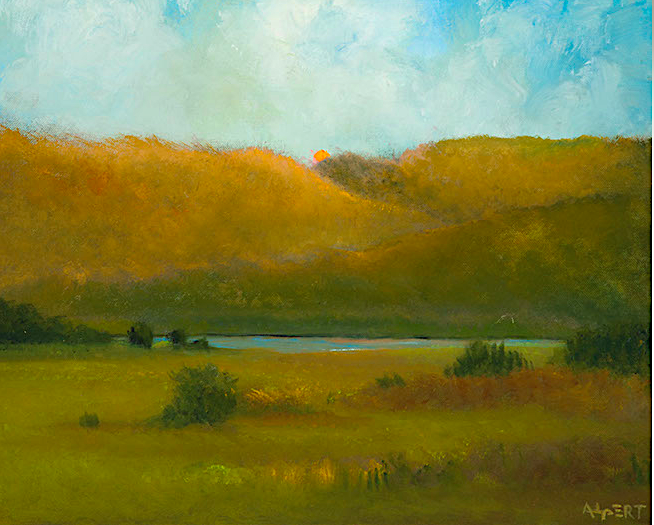

Steve Alpert: Landscapes are where I began. Initially, I was attracted to the landscapes of the Impressionists. They spoke to me, the bright colors, the freedom to ignore any established norms at that time. I also was attracted to on-location painting. Around the same time I took a 6,000 mile solo hitchhiking trip to experience the American West. The confluence of those two factors took me a long way into landscape.

The military paintings began in November 2003 when I learned about two of our Blackhawk helicopters colliding in mid-air over northern Iraq. It grabbed my attention in a profound way and I wanted to make a large painting of a Blackhawk helicopter in honor of the seventeen soldiers we lost that day. That first Blackhawk painting gave way to a series of paintings of Blackhawks. My wife came into my studio a month or so later, looked at all the Blackhawk paintings and said, “What are you going to do with all all these paintings?” To which I replied, “I have no idea.” A few years later after a visit to the old Walter Reed Hospital to thank wounded soldiers, I realized my military paintings had a job to do; to raise consciousness and financial support for veterans. Also, this was a way for me to pay back for service I owe for not having served in uniform during the Vietnam War years. Not having served in uniform is my greatest regret in my life. I have been making these paintings ever since.

Portrait painting is the most challenging aspect of my work. I am attracted to the notion of storytelling having been a TV producer/director/editor in my earlier career. It is compelling to make a portrait that tells a person’s life story in one stationary image. An ultimate challenge in arranging minerals on a canvas to tell a life story. To make that person come alive. I am endlessly fascinated by the process of making a person come alive in oil paint. There is a moment in making each portrait where I “have that person in my hand.” It is deeply satisfying to capture that person’s essence. It is quite a thrill.

PZ: What is the most challenging aspect of your creative process?

SA: Making paintings is joyful, it is romance and it is adventure. It is my pleasure, and my passion, so it is never really what I would call work. When I complete a painting that I know is very good then have to move into the discipline of, “where does it go.” I need to be strategic in whose eyes I can get on the image. Making the work is one thing, getting the work out there is quite another. Two completely different skill sets. For me, when I complete a painting I consider to be a major work that I have initiated for the pure joy of its’ making, the issue is having to have that piece around weeks, months and sometimes years before they find their home. I had one major piece hang around my studio for years before it was called to duty as inspiration for a stage play, and eventual purchase. Every time I entered my studio I would see that big canvas sitting in my cubby space — it gave me pain every time I saw it just sitting there, for years. I think this a well known issue for many artists. This comes with the territory of us artists who just have to make our work because they simply must be made.

PZ: Do you have any particular goal in mind when you start a new painting?

SA: My only real goal is to give it my all. In every session I pour myself into the work with discipline and a sense of freedom at the same time. The goal for the portraits is very unique. Portraits are very specific, and yet I need to find that balance in allowing myself to freely experience adventurous spirit in being free to make decisions about composition, the eyes, clothing and the all important background that must compliment and support the image of the person. There is a painting I made last year that was from a photo I took on a trip to Jerusalem. A young boy joyously bounds through a fountain blissfully unaware of the deadly conflicts surrounding him. My goal was to capture this moment that grabbed me as I walked by a footbridge above the fountain. I love the painting, and it has grabbed a lot of attention though has not yet found it’s home…

Actual Proof, 16″ x 20,” oil on canvas

Actual Proof, 16″ x 20,” oil on canvas

PZ: How do you know when the painting is finished?

SA: Twenty years of working in watercolor taught me when a painting is finished. One stroke too many in watercolor ruins the work. Oil is totally forgiving and and you can continue forever if you choose. I’ve been doing this long enough to know when i am satisfied. Perfectionism is the enemy. All works of art are flawed, that is the nature of art making. I have learned to accept that, although I admit to fiddling and tweaking in the portrait work. The great Indian master rug weavers always make a deliberate “error” because, only God is perfect. I like that notion a lot.

PZ: How did your practice change over time?

SA: When I began I worked almost solely in non-objective painting. I would begin with a slash of color, a wash, or a line. And then go from there, not thinking too much until I arrive at a stopping place. I would step back, and evaluate on what is happening on the canvas. Maybe I’d return the next day and then dive in with fresh eyes. In paintings where I have a definite story to tell, I take photograph after each work session. Later that night I would look at it and would know what I wanted to accomplish in the next session. Although I have a clear goal in my mind about wanting to tell the life story of my portrait subject, I still want to allow myself enough freedom to create a certain newness in each piece. I want to be constantly refining my vision as a painter, canvas after canvas. My overarching philosophy is to always be growing as an artist, to sharpen my vision and ability to implement that vision with paint and brush.

PZ: How would you describe yourself as an artist?

SA: I would describe myself as a storyteller. Paint, brush, canvas is my main medium. I worked in TV as producer/director/editor. I have produced three stage plays, one Broadway show and two off-Broadway productions. I wrote one book and am currently working on two more. It is all about being passionate about storytelling. In painting, the mission is to tell the stories in the most elegant way in oil paint. I am forever motivated and excited. My paintings are my personal ambassadors to the world.

PZ: What is art for you?

SA: Art for me is anything that takes me to somewhere in my mind that I may already know about and expands my perceptions. Maybe don’t know anything about the story being told, but it confronts me, entertains me, or makes me think about something in a way I may have not ever thought before. Art — good art — can be uplifting, confrontational or soothing. Ask art object can be anything from a beer can that has been flattened by a vehicle in a way that is, “artistic,” all the way to a Matisse master work. And everything in between.

PZ: Which artists are you most influenced by?

SA: Henri Matisse, Gerhard Richter, Claude Monet, John Singer Sargent, Alan Atwell, Joan Miro…

PZ: What are you working on now?

SA: I am currently working on a series of twelve large portraits of women military veterans for a project called, Proudly She Served, www.proudlysheserved.com. We will reveal the paintings in a launch event at the Military Women’s Memorial museum at the base of Arlington National Cemetery in Washington DC in March 2022. I am also working on a large copy of one of my favorite Matisse paintings, The Goldfish Bowl, and a series of landscapes as well. I am also working to find a way to get my portrait of Senator John McCain into the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC. Plus, I have been leading an art-making workshop for Veterans at Fordham University in New York City. It is deeply rewarding. The irony her is the the Veterans have tight me much more than I have taught them.

PZ: How does the pandemic influence your work and sensibility?

SA: The pandemic has given me a lot of quiet time to work. Especially back in in the Spring, New York City was especially quiet. Instead of traffic and street noise in my NYC studio, all I could hear were birds enjoying a new and glorious Spring. It was actually quite heavenly except for the ambulance sirens which brought on that feeling of dread because those emergency vehicles were taking covid patients to the hospital. But, if I could discipline myself to keep key focus on the work, I was good. I think these last months have been a great gift to so many of us artists. Kind of perverse in a way, but I know there will be many artists who would relate to this this time of great quiet that has given us all a lot of time to think, reflect, and to work.